Project's main research question:

How can the design of elements and mechanics of the parallel digital worlds build mental strings in between the worlds (and evoke different types of experience from the players when interacting with the 3D game environment)?

Further questions to elaborate on the process:

• How can the gamers’ user type affect their interactions with the world(s)?

• What kind of different emotions could the way the parallel worlds are built in An Ended World (with everything in them, including sounds, lighting and characters) evoke in players? What is these emotions’ relation to different types of immersion in video games in this setting?

• In which way does the design of the touchpoints (both the literal scripted switch between the 3D environments and the emotional / imaginative connection from the player) change the way the worlds are perceived or made sense of?

• What kind of different mental strings can the design of the digital world(s) form?

What is an Ended World?

The common themes one can associate with An Ended World (and now I will be taking inspiration from science fiction and (post-)apocalyptic stories) is downfall: the decline of moral values and personal freedom, decay, destruction and death. However, my approach to the phrase is a bit more open - besides the classical post-apocalyptic version of a destroyed Earth/human society, I preferred to have an open mind. An Ended World might as well mean an end of an era in a very specific context. Thinking in an even smaller scale – a death of a person could also be called an end of a world if we consider one’s consciousness a world of its own.

Overall, whatever the different scales of an end might be, they deal with similar powerful emotions: sadness, fear, anger, disbelief and morbid curiosity.

Speculative Design Workshop

Pre-workshop: Playing with existing parallel digital worlds in computer games in this setting (Dishonored 2 Chapter: Aramis Stilton's Mansion & Bioshock 2 mission through the eyes of a Little Sister)

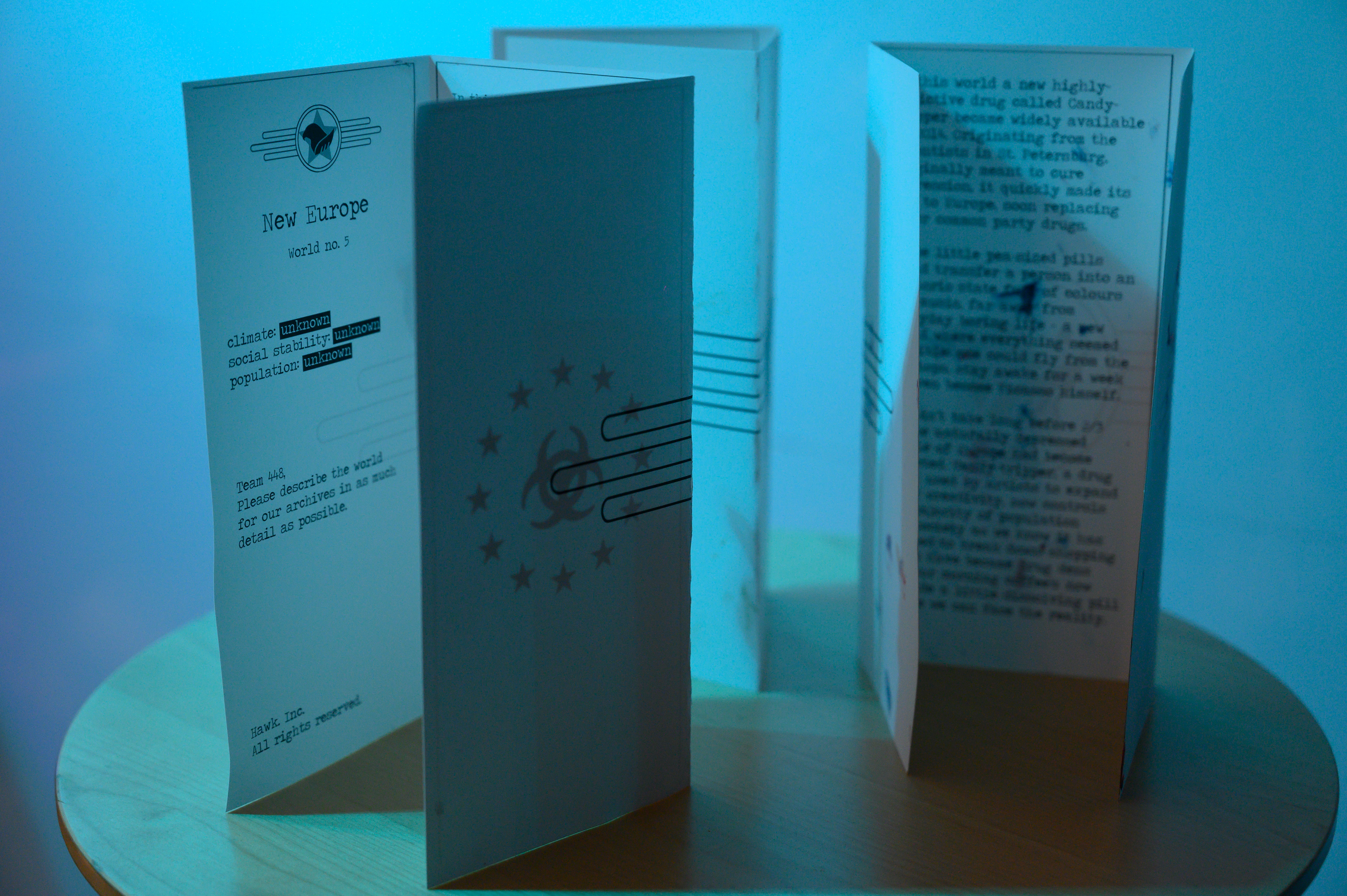

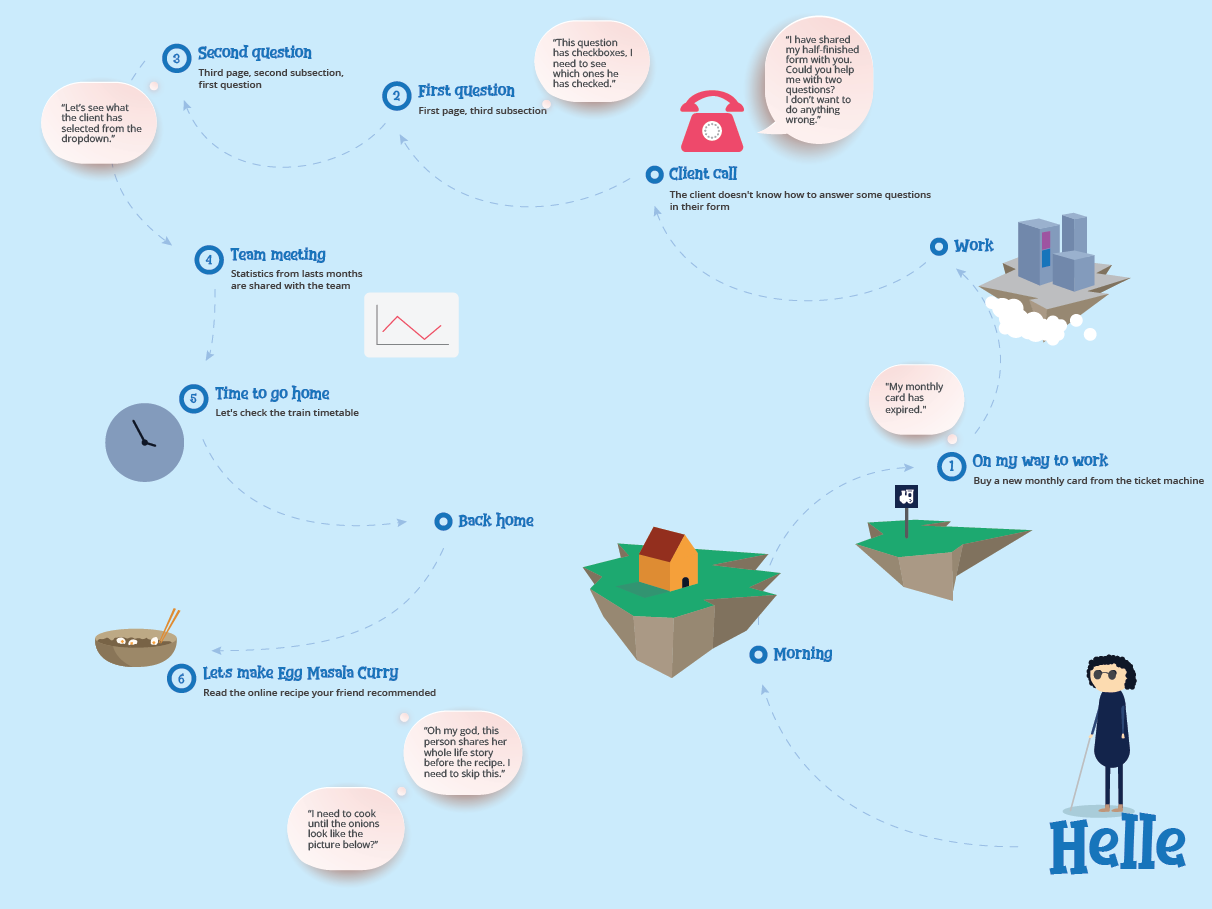

The first workshop for the project took inspiration from Markussen & Knutz's work from Kolding School of Design on mixing design with literary practises. For my workshop I chose a very open and creative path for my designed tasks. The participants were handed three cases of an Ended World, created by the designer, from which they had to choose one. Their mission was then to create individual "story worlds" of the physical environment around them (in this case an office) based on the given information.

The purpose was to see how different minds, while presented with an “alternative parallel world” set in a particular setting started making sense of their surroundings, described the world and found their roles and purposes of the elements around them.

Chosen "Ended World" scenario

World no. 105.4637.056: Candy-tripper:

In this world a new highly addictive drug called Candy-tripper became widely available in 2014. Originating from the scientists in St. Petersburg, originally meant to cure depression, it quickly made its way to Europe, soon replacing other common party drugs.

These little pea-sized pills could transfer a person into an euphoric state full of colours and music, far away from everyday boring life – a new world where everything seemed possible: one could fly from the rooftops, stay awake for a week or even become Picasso himself.

It didn’t take long before 2/3 of the naturally depressed people of Europe had become addicted. Candy-tripper, a drug first used by artists to expand their creativity, now controls the majority of population and society as we know it has started to break down: shopping malls have become drug dens and our morning coffee’s now include a little dissolving pill before we can face the reality.

These little pea-sized pills could transfer a person into an euphoric state full of colours and music, far away from everyday boring life – a new world where everything seemed possible: one could fly from the rooftops, stay awake for a week or even become Picasso himself.

It didn’t take long before 2/3 of the naturally depressed people of Europe had become addicted. Candy-tripper, a drug first used by artists to expand their creativity, now controls the majority of population and society as we know it has started to break down: shopping malls have become drug dens and our morning coffee’s now include a little dissolving pill before we can face the reality.

The workshop participants were then asked to take the role of a wormhole-jumping scientist from an international corporation Hawk. Inc., specialized in mapping out parallel worlds and describing them to the imaginary archives. The roleplay helped the participants to better answer the questions like why? – instead of just describing the imaginary environment they were supposedly in, the participants were also forced to think why something would be the way they see it.

4 People, 4 Worlds

The Mental Threads Between Worlds

On the left we can see the structured “physical” world with objects, character models, etc. On the right the same world exists but through a more mental perspective. Even though the focus of this project is on the latter, the two domains are highly intertwined – the mental strings cannot form without the physical.

Shifting the focus back to digital worlds:

On the left we can see the layout of two parallel worlds, both in physical and mental setting. The connections between them happen through threads and scripted switches (literal scripted event when the player enters the parallel).

Using the term mental threads in this case fits well since a thread, by its nature, can be tightened, loosened and broken, while the scripted switch, however, is decided by the designer and lies in the technical aspects of a game.

How are the mental threads formed?

When talking about the connections between two parallel worlds, it is important to expand on the attributes that have the potential to create those threads in the user’s mind, especially when looking at the interaction through the lens of “good” immersion and different forms of experience. It is also good to remember that this research revolves around the idea of An Ended World, that has its own influence on the threads formed – focus on background, story and the feelings of “end”.

The full list of attributes will be presented later.

The attributes influence on creating different forms of immersion that have the capacity to create threads and result in various types of experiences when interacting with the game. Note: even though the left side states “physical”, they need to have some connection to the “mental” in order to create the threads (previous picture)

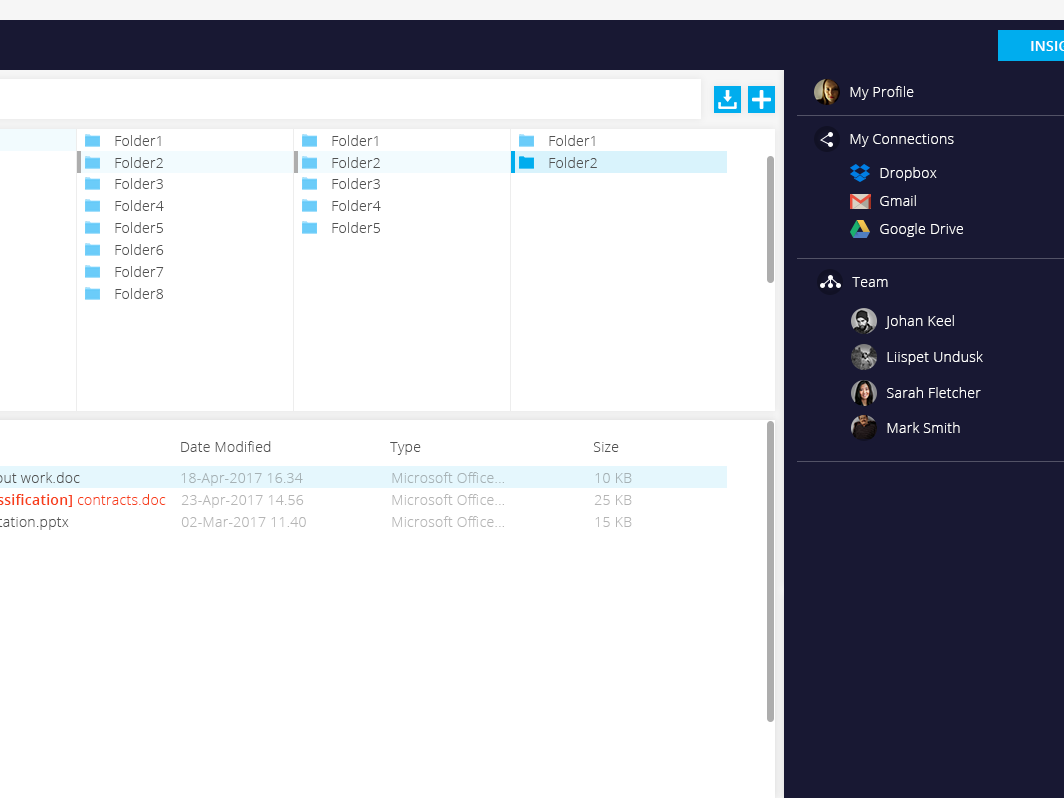

Testing Out My Hypothesis Through a G.E.C.K. Prototype

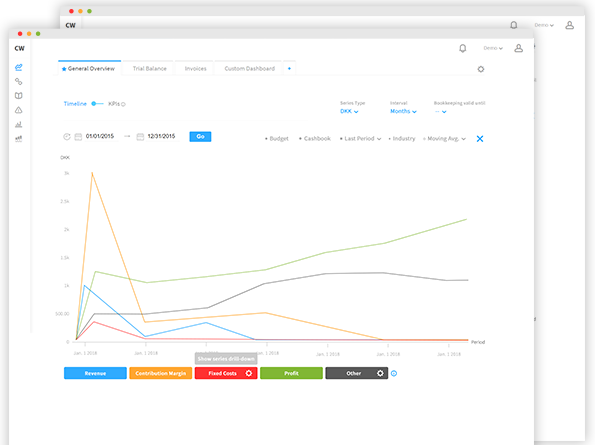

Due to the very short time scale of this project it would’ve been hard to build a working digital environment from scratch, which is why it made sense to take a glance at already existing games and the resources they could provide. In order to test out my theories of series of attributes mentioned in the last chapter, I decided to build a digital environment for the game Fallout 4 by using Bethesda’s modification kit called G.E.C.K. In the end 4 different versions were built and playtested.

In order to place my prototype outside the existing game background/lore, the two parallel worlds were built as a separate cell from the rest of the game world.

The parallels are created as two opposite rooms mirroring each other, divided by a long hallway.

Version 1 - The Basics

I decided to go with a domestic setting: the two rooms were set up as one being very bright and new, while the other looking destroyed and dangerous. All the furniture and objects were placed in the same spot, just mirroring each other, so it was clear that it was, indeed, the same environment. The corridor between the two acted as a “descendance” – the more towards the Ended World the character walked, the “darker” the atmosphere turned.

When it comes to characters, the “light” held a generic male NPC with no real interaction (clicking on him just made him speak some short random phrases) while the “dark” was populated with a single ghoul (basically a zombie), supposed to represent the “other” version of the NPC.

Overall, there weren’t too many possibilities to interact with the world, rather just observe. From feedback the players understood that the two rooms were opposites of each other but since the “switch” happened gradually (walking down the hallway) the correlation between the worlds became distant. The players could see that one world mirrored the other, but the strings that formed were loose and didn’t offer much tension.

Version 2 - The Immediate Switch

In the second version the parallel worlds were divided into two different cells that were connected by “doors” – the scripted switch in between.

As the idea was to make the whole environment highly interactive (meaning that the player could click around objects and be greeted with some sort of response from the game) the switches were hidden into everyday objects around the apartment in order to evoke the element of surprise. The doors varied in the cells, so a teleporting flowerpot in one would not behave the same way in the other world and so on. A cell held three switches, one in each room.

The same character in two worlds.

Baby's crib in two worlds.

Version 3 - The Mental, Narrative World

It is worth noting that I didn’t want to create a story set too much in stone in order to see people’s own reactions and mental narratives that could emerge from the setting, but in order for that to happen, some story in the prototype had to still be created by me. Overall the setting was perceived through a female character in a domestic atmosphere with her husband, baby and a housecat. Through small clues in the world the player could discover that not everything was as nice as it looked at first with small hints to a drained marriage and domestic abuse

In order to tell that narrative, I made use of not only the atmosphere, look of objects and other things considered in the previous versions but also by adding the possibility of interaction with the world. Many times the objects that could be clicked on acted differently in the two worlds, playing on the idea of comparison.

Version 4 - Adding a Quest

Even though the atmosphere and the strong comparisons worked well in thread-weaving, a large potential was missed just because there was nothing indicating what the player had to do or what

their goal was, resulting in aimless wondering and often just spending 90% in one world, looking for a way out. In order to counter that I needed a way for the game to slightly nudge the player in the right direction: make them jump between worlds and find clues necessary to build a narrative in their head. The quest would end with the player escaping through the “dark” into a destroyed outside world.

their goal was, resulting in aimless wondering and often just spending 90% in one world, looking for a way out. In order to counter that I needed a way for the game to slightly nudge the player in the right direction: make them jump between worlds and find clues necessary to build a narrative in their head. The quest would end with the player escaping through the “dark” into a destroyed outside world.

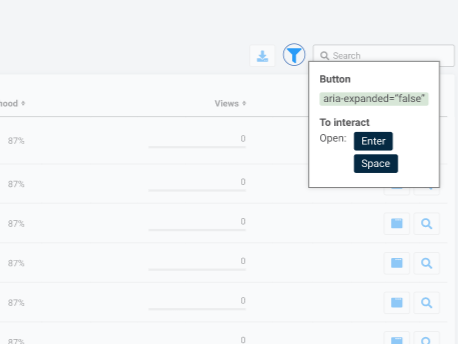

A very direct order from the game has a little marker on the top to bring attention to it (left). A more open order just tries to set a direction – “Find a way out” (right).

A short video of the mod used for this project.

The Weavers of Mental Threads

“Physical” 3D rendered world attributes:

The look, design and purpose of audio-visual objects (3D-/character models, lights, sounds) – […] the effect the physical objects can provide will only work when channelled through the mental attributes. […] this is still the easiest way for the designer to build a world based on the existing norms in our culture. These norms meaning some agreed values that would most likely produce a desired effect (closely tied to the Cultural background attribute).

Character behaviour and AI – Even in a digital environment people still tend to be drawn to other human (or just alive) characters. The differences between worlds were more memorable when they were present in the living beings (husband, baby, cat). I can claim that we can reflect this to empathy and the motivation of relatedness, in this case, indeed, of fictional characters not other players.

Frequency of the switch – […] If the game mechanics (for instance the set up of a quest) or its level design didn’t support the switch to happen in certain periods of time, the player could end up spending too long in one world. It was also noted that the strings formed were much looser when the player spent too much time in one rather than in both worlds equally. […]

Worlds’ connection to each other – When changing something in one world the player almost expects it to have an effect in the other, no matter the worlds’ actual relation to each other. […]

Interactivity of objects – In this case I mean that the choice of points for interaction can also act as a guide to creating mental threads. What can be clicked on, what can be moved? This could also work as a quest – setting a list of objectives the player must interact with, that in turn will guide them through the area. […]

Mental, narrative world attributes:

Atmosphere of the environment – The type of feeling(s) the game environment is trying to make the player experience. The change in atmosphere was the first thing players noted when first entering the “dark” world. […]

The narrative – Also includes the background, lore, stories within. This is what the designer decides is the story. […]

Belief of the world – The world has to be grounded in something, very connected with the narrative and the cultural experiences / type of personality of the player. Important factor to the player’s interaction with the worlds – when the user does something, they expect it to have an impact, often also in the world they were not currently present in. Actions need to have meaning.

Cultural background – The player’s connection with the “real” world and their experiences in it. The cultural differences and symbolism play a role here. This is a hard attribute to pin down as it can be very subjective. […]

Strong comparison – In order to pull a strong thread, the comparison between the two worlds/objects must be explicit. The stronger the comparison, the tighter the thread. […]

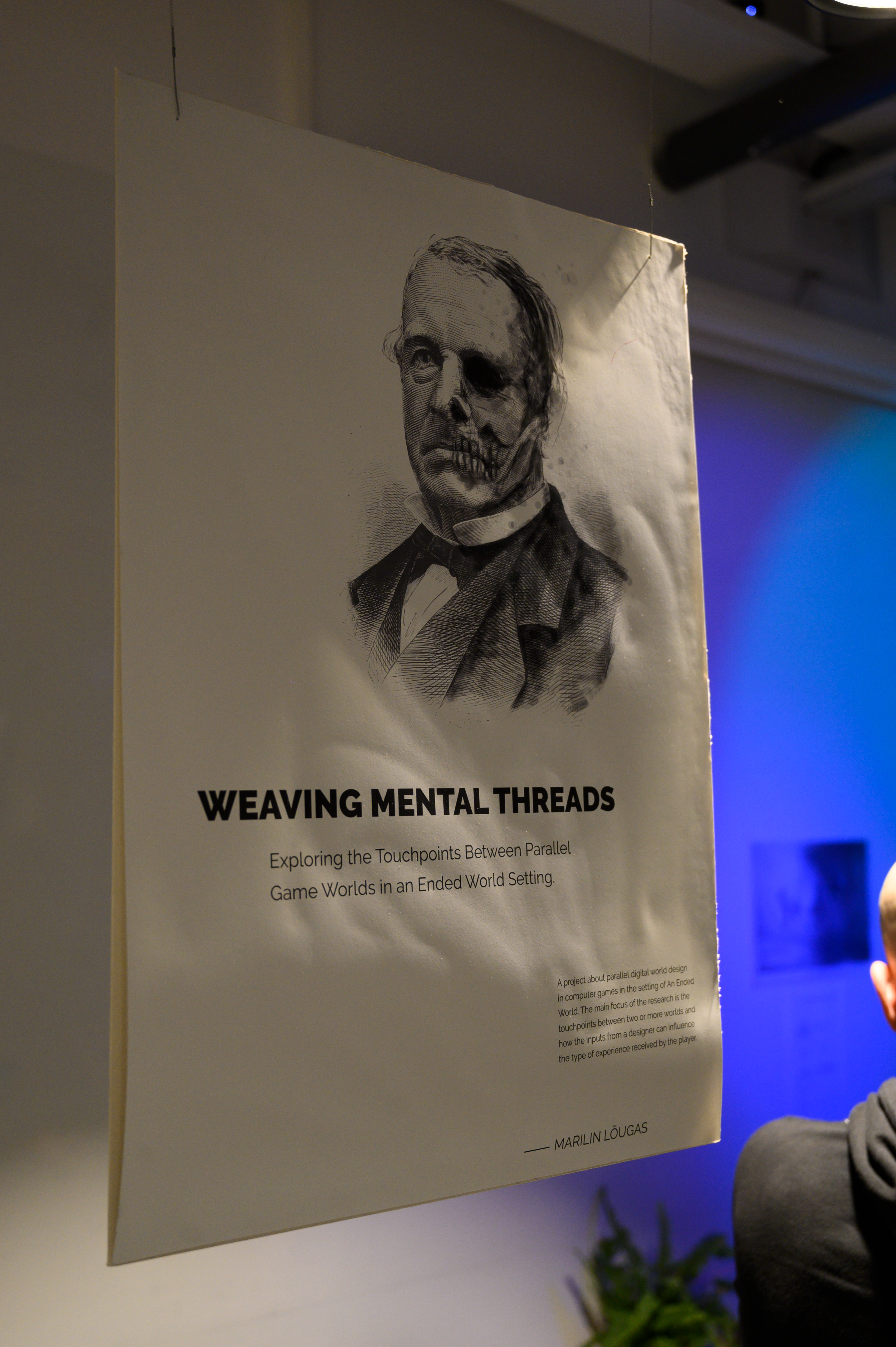

A series of images from the final exhibition: